[Oath Keepers}

[Oath Keepers}

[Oath Breaker..!]

by Bill Federer

[Oath Breaker..!]

by Bill Federer

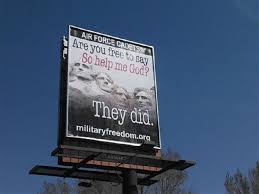

Why has the tradition in America been for oaths to end with “So Help Me God”?

The military’s oath of enlistment ended with “So Help Me God.”

The commissioned officers’ oath ended with “So Help Me God.”

President’s oath of office ended with “So Help Me God.”

Congressmen and Senators’ oath ended with “So Help Me God.”

Witnesses in Court swore to tell the truth, “So Help Me God.”

Even Lincoln proposed an oath to be a United States citizen which ended with “So Help Me God.”

On

DECEMBER 8, 1863, Lincoln announced his plan to accept back into the

Union those who had been in the Confederacy with a proposed oath:

“Whereas

it is now desired by some persons heretofore engaged in said rebellion

to resume their allegiance to the United States…Therefore, I, Abraham

Lincoln, President of the United States, do proclaim, declare, and make

known to all persons who have, directly or by implication, participated

in the existing rebellion … that a full pardon is hereby granted to

them…with restoration of all rights of property … upon the condition

that every such person shall take and subscribe an oath … to wit:

“I, ______, do solemnly

swear, in the presence of ALMIGHTY GOD, that I will henceforth

faithfully support, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United

States and the Union of the States thereunder, and that I will in like

manner abide by and faithfully support all acts of Congress passed

during the existing rebellion with reference to slaves… and that I will

in like manner abide by and faithfully support all proclamations of the

President made during the existing rebellion having reference to slaves…

SO HELP ME GOD.”

A similar situation was faced by Justice Samuel

Chase, who was the Chief Justice of Maryland’s Supreme Court in 1791,

and then appointed by George Washington as a Justice on the U.S. Supreme

Court, 1796-1811.

In 1799, a dispute arose over whether an Irish

immigrant named Thomas M’Creery had in fact become a naturalized U.S.

citizen and thereby able to leave an estate to a relative in Ireland.

The court decided in M’Creery’s favor based on a certificate executed before Justice Samuel Chase, which stated:

“I,

Samuel Chase, Chief Judge of the State of Maryland, do hereby certify

all whom it may concern, that … personally appeared before me Thomas

M’Creery, and did repeat and subscribe a declaration of his belief in

the Christian Religion, and take the oath required by the Act of

Assembly of this State, entitled, An Act for Naturalization.”

An

oath was meant to call a Higher Power to hold one accountable to perform

what they promised. . . . Courts of Justice thought oaths would lose

their effectiveness if the public at large lost their fear of the God of

the Bible who gave the commandment “Thou shalt not bear false witness.”

New York Supreme Court Chief Justice Chancellor Kent noted in

People v. Ruggles, 1811, that irreverence weakened the effectiveness of oaths:

“Christianity

was parcel of the law, and to cast contumelious reproaches upon it,

tended to weaken the foundation of moral obligation, and the efficacy of

oaths.”

George Washington warned of this in his Farewell Address, 1796:

“Let

it simply be asked where is the security for prosperity, for

reputation, for life, if the sense of religious obligation desert the

oaths, which are the instruments of investigation in the Courts of

Justice?”

In August of 1831, Alexis de Tocqueville observed a court case:

“While

I was in America, a witness, who happened to be called at the assizes

of the county of Chester (state of New York), declared that he did not

believe in the existence of God or in the immortality of the soul.”

The judge refused to admit his evidence, on the ground that the

witness had destroyed beforehand all confidence of the court in what he

was about to say.

The newspapers related the fact without any further comment. The

New York Spectator

of August 23, 1831, relates the fact in the following terms: “The court

of common pleas of Chester County (New York), a few days since rejected

a witness who declared his disbelief in the existence of God.”

The

presiding judge remarked, that he had not before been aware that there

was a man living who did not believe in the existence of God; that this

belief constituted the sanction of all testimony in a court of justice:

and that he knew of no case in a Christian country, where a witness had

been permitted to testify without such belief.'” Oaths to hold office

had similar acknowledgments.

The Constitution of Mississippi,

1817, stated: “No person who denies the being of God or a future state

of rewards and punishments shall hold any office in the civil department

of the State.”

The Constitution of Tennessee, 1870, article IX, Section 2, stated:

“No

person who denies the being of God, or a future state of rewards and

punishments, shall hold any office in the civil department of this

State.”

The Constitution of Maryland, 1851, required office

holders make “[a] declaration of belief in the Christian religion; and

if the party shall profess to be a Jew the declaration shall be of his

belief in a future state of rewards and punishments.”

In 1864, the

Constitution of Maryland required office holders to make “[a]

declaration of belief in the Christian religion, or of the existence of

God, and in a future state of rewards and punishments.”

The Constitution of Pennsylvania, 1776, chapter 2, section 10, stated:

“Each

member, before he takes his seat, shall make and subscribe the

following declaration, viz: ‘I do believe in one God, the Creator and

Governor of the Universe, the Rewarder of the good and Punisher of the

wicked, and I do acknowledge the Scriptures of the Old and New Testament

to be given by Divine Inspiration.'”

The Constitution of South

Carolina, 1778, article 12, stated: “Every…person, who acknowledges the

being of a God, and believes in the future state of rewards and

punishments… (is eligible to vote).”

The Constitution of South Carolina, 1790, article 38, stated: “That

all persons and religious societies, who acknowledge that there is one

God, and a future state of rewards and punishments, and that God is

publicly to be worshiped, shall be freely tolerated.”

Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court stated in

Commonwealth v. Wolf (3 Serg. & R. 48, 50, 1817:

“Laws

cannot be administered in any civilized government unless the people

are taught to revere the sanctity of an oath, and look to a future state

of rewards and punishments for the deeds of this life.”

It was

understood that persons in positions of power would have opportunities

to do corrupt backroom deals for their own benefit.

But if that

person believed that God existed, that He was watching, and that He

would hold them accountable in the future, that person would hesitate,

thinking “even if I get away with this my whole life, I will still be

accountable to God in the next.” This is what is called “a conscience.”

But

if that person did not believe in God and in a future state of rewards

and punishments, then when presented with the temptation to do wrong and

not get caught, they would give in.

In fact, if there is no God, and this life is all there is, they would be a fool not to.

This

is what President Reagan referred to in 1984: “Without God there is no

virtue because there is no prompting of the conscience.”

William

Linn, who was unanimously elected as the first U.S. House Chaplain, May

1, 1789, stated: “Let my neighbor once persuade himself that there is no

God, and he will soon pick my pocket, and break not only my leg but my

neck. If there be no God, there is no law, no future account; government

then is the ordinance of man only, and we cannot be subject for

conscience sake.”

Sir William Blackstone, one of the most quoted authors by America’s founders, wrote in

Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765-1770):

“The

belief of a future state of rewards and punishments, the entertaining

just ideas of the main attributes of the Supreme Being, and a firm

persuasion that He superintends and will finally compensate every action

in human life (all which are revealed in the doctrines of our Savior,

Christ), these are the grand foundations of all judicial oaths, which

call God to witness the truth of those facts which perhaps may be only

known to Him and the party attesting.”

When Secretary of State

Daniel Webster was asked what the greatest thought was that ever passed

through his mind, he replied “My accountability to God.”

Benjamin Franklin wrote to Yale President Ezra Stiles, March 9, 1790:

“The soul of Man is immortal, and will be treated with Justice in

another Life respecting its conduct in this.” Benjamin Franklin also

wrote:

“That there is one God, Father

of the Universe… That He loves such of His creatures as love and do good

to others: and will reward them either in this world or hereafter, that

men’s minds do not die with their bodies, but are made more happy or

miserable after this life according to their actions.”

John Adams wrote to Judge F. A. Van der Kemp, January 13, 1815:

“My

religion is founded on the love of God and my neighbor; in the hope of

pardon for my offenses; upon contrition… In the duty of doing no wrong,

but all the good I can, to the creation, of which I am but an

infinitesimal part. I believe, too, in a future state of rewards and

punishments.”

John Adams wrote again to Judge F. A. Van de Kemp, December 27, 1816:

“Let

it once be revealed or demonstrated that there is no future state, and

my advice to every man, woman, and child, would be, as our existence

would be in our own power, to take opium. For, I am certain there is

nothing in this world worth living for but hope, and every hope will

fail us, if the last hope, that of a future state, is extinguished.”

John Adams wrote in a

Proclamation of Humiliation, Fasting, and Prayer, March 6, 1799:

“No

truth is more clearly taught in the Volume of Inspiration… than…

acknowledgment of… a Supreme Being and of the accountableness of men to

Him as the searcher of hearts and righteous distributor of rewards and

punishments.”